Frauke Kreuter, Esther Kim, Sarah LaRocca, Katherine Morris, Christoph Kern, Andres Garcia

December 21, 2020

Context

The Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey, which launched in April, 2020, is currently the largest ongoing public health data collection effort related to COVID-19. The survey is led by the University of Maryland and Carnegie Mellon University in partnership with Facebook Data for Good. Everyday, the survey is fielded in 200+ countries and territories in 50+ languages, and asks a variety of questions on symptoms, testing, preventive behavior including mask-wearing, vaccines, risk factors, mental health, and more. All of the data are aggregated daily and are made available on our API (click here for the international data; here for the US data). Previously, we highlighted the release of our data on face mask use, and demonstrated that the prevalence of mask-wearing varies considerably across the globe.

We recently released a new set of aggregated data on economic indicators, which will provide new insights into how individuals have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. Economic concerns due to COVID-19 are widespread; however, it has been challenging to examine the global prevalence and trends related to personal economic anxiety due to the lack of long-term multi-national data on the economic hardships that individuals are concerned about throughout the pandemic. Using our new data from the Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey, which addresses many of these concerns, we explored a few questions related to the prevalence and trends of economic anxiety:

1.What is the prevalence of household financial worry (financial anxiety) around the world?

2.Does financial anxiety reflect COVID-19 cases?

3.How does individual financial anxiety correlate to government responses to COVID-19?

New Data on Economic Anxiety from the Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey

The following questions were added to the international version of the UMD Global CTIS on July 3, 2020, and the aggregated responses to these questions are now publicly available on our API:

1.How worried are you about your household’s finances in the next month?

2.Do any of the following reasons describe why you are worried about your household’s finances in the next month1?

3.How worried are you about having enough to eat in the next week?

4.In the last 7 days, did you do any work for pay, or do any kind of business, farming, or other activity to earn money, even if only for one hour?

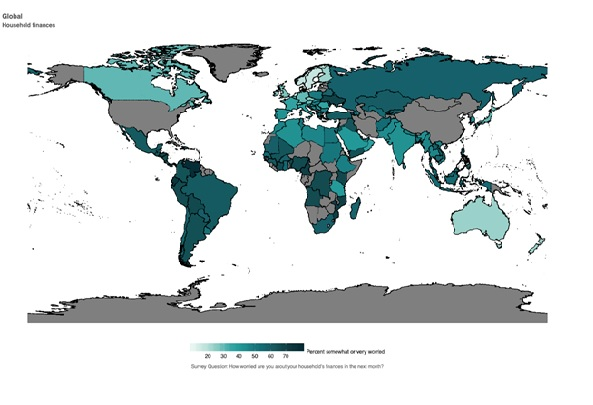

In the following analysis, we examine financial anxiety using the aggregates from the first question. We defined financial anxiety as being ‘very worried’ or ‘somewhat worried’ about one’s household finances in the next month. All data used in this analysis are from the international version of the UMD Global CTIS, thus, excludes data from the US. In total, we included 18,001,739 responses collected between July 1, 2020 and November 30, 2020 from 114 countries and territories where sufficient responses were collected and population figures allowed re-weighting of the data to provide country estimates.

Prevalence of Financial Anxiety

The figure above depicts the period prevalence of financial anxiety from November across 114 countries. There was some variation in the proportion of those who are somewhat or very worried about their household finances across the countries. In general, countries in Europe had the lowest proportion of those who were worried (mostly <50%), whereas in Central/South American countries had the highest proportion (mostly >50%). In Africa and in the Asia/Pacific region, this proportion varied depending on the country.

In addition to cross-country differences, we also found that there were some variations across regions within countries. (Note: the Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey employs stratified sampling to randomly sample individuals within the administrative boundaries of each country, for example, Federal States within Germany. This means that we are able compare aggregated responses within countries.) For example, in Indonesia, those living in central and eastern subnational regions were less worried about household finances as compared to those living in the western regions of Sumatra and Java, which include the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (figure below).

Financial Anxiety and COVID-19 Cases

A unique aspect of the UMD Global CTIS is its repeated cross-sectional daily design, which allows us to examine trends throughout time for the majority of the variables collected by the survey. We therefore examined how changes in financial anxiety may be related to daily COVID-19 cases from July until November, and found that in some countries, there seems to be a relationship between COVID-19 cases and financial worry. Below, we illustrate below a few useful cases, keeping in mind that causality cannot be inferred from our descriptive analysis.

In Vietnam, South Korea, and South Africa, we observed that the trends of financial anxiety closely mirror the daily country-level COVID-19 cases (figure above). The sudden increase in the proportion of those indicating financial anxiety seem to shortly follow the sudden rise in COVID-19 cases in these countries, which happens around August for Vietnam, late-August and early-September for South Korea, and late-July for South Africa. This suggests that it is possible that spikes in cases may trigger worries related to personal finances; however, we encourage readers to investigate these trends in future studies. (If you have country-level knowledge, we encourage you to check out our data!)

In Germany and France, we observed a weaker relationship between financial anxiety and COVID-19 cases. While the increases in cases seem to align with higher proportions of those indicating financial worry, there were only small variations in financial anxiety across time.

Correlation between Financial Anxiety and Government Policies

We additionally examined whether financial anxiety correlates with government responses to COVID-19 from July until November. More specifically, we were interested in examining whether strict COVID-19 related policies would be correlated with more (or less) concerns related to personal finances. To conduct this analysis, we used the Government Stringency Index created by the University of Oxford. This index is derived from nine policies related to school and workplace closures, cancellation of public events and gatherings, public transportation closures, stay-at-home orders, public information campaigns, and restrictions on travel. The score ranges from 0-100, and a higher score indicates stricter government response. For ease of illustration, we included a subset of the countries based on sample size (effective sample size ≥ 5000).

Our results suggest that the proportion of those worried about personal finances is moderately correlated with the Government Stringency Index, especially in the earlier months (r ≥0.6 from July until September). Interestingly, this correlation decreases over the months (r=0.39 in November). It seems that this may be influenced by a decreasing variation in worries across countries over time.

What’s Next?

Our analysis demonstrates that 1) economic anxiety varies across countries and within countries, 2) financial anxiety mirrors COVID-19 cases over time in some countries, and 3) financial anxiety seems correlated with government policies related to COVID-19, though this relationship weakens over time. All of these relationships require further explorations and many more questions can be answered with these data combined with other data sources: How does food insecurity and employment change over time? Which types of individuals are the most worried and why? Which factors are the strongest drivers of food insecurity, financial anxiety, and employment? Furthermore, it would be useful to examine all of these questions further across countries and territories or across subnational regions to better understand how policies implemented both before and during the pandemic affect individual economic anxiety and its correlation with the spread of COVID-19.

The University of Maryland hosts all of the data used in this analysis and much more on their API. Details on the study design of the UMD Global CTIS including the sampling and weighting methodology has been published previously (read more about our partnership and study design, as well as sampling and weighting methods). The US version of the UMD Global CTIS and their aggregated data are also available for public use (link). Individual-level data are available upon request from researchers (link). A list of other publications using these data are available on the Facebook Data for Good Website, as well as on this blog (link).

Updated on December 10, 2021:

Note on the limitations of the survey: The Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey (CTIS), formerly known as the COVID-19 Symptom Survey, is subject to several limitations, many of which are common to web surveys. Anyone using the data to make policy decisions or answer research questions should be aware of these limitations, which are detailed here.

Given these limitations, we recommend using CTIS data to highlight trends across time or differences between groups, rather than focusing on total population estimates. We also strongly encourage users with access to the individual level data to consider whether additional corrections are needed to the weights, whether multiple imputation is needed to correct for missing data, and whether augmenting the survey with data collected from other sources, such as official data on testing, hospitalizations, and vaccinations or surveys that include respondents that do not have access to the internet, is needed for their research question(s)

To stay updated on survey questionnaire revisions and errors related to the survey instrument and data processing, sign up for our mailing list and check the Notices and Updates page regularly.